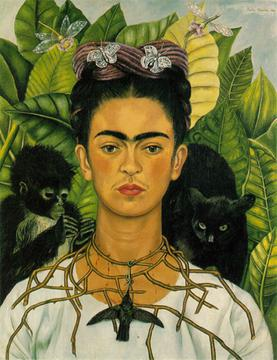

Frida Kahlo (1907–1954) was a Mexican artist known for her deeply personal and surrealist paintings that often explored themes of identity, post-colonialism, gender, and pain. Her works are characterized by vivid colors, symbolic imagery, and an unflinching portrayal of her physical and emotional struggles. Kahlo’s life was marked by personal hardship, including a severe bus accident as a child and chronic health issues afterwards, which influenced her art profoundly throughout decades. Kahlo’s paintings frequently depict her own experiences, emotions, and cultural heritage. Her distinctive style blends Mexican folk art with surrealism, resulting in a unique visual language that continues to captivate audiences worldwide.

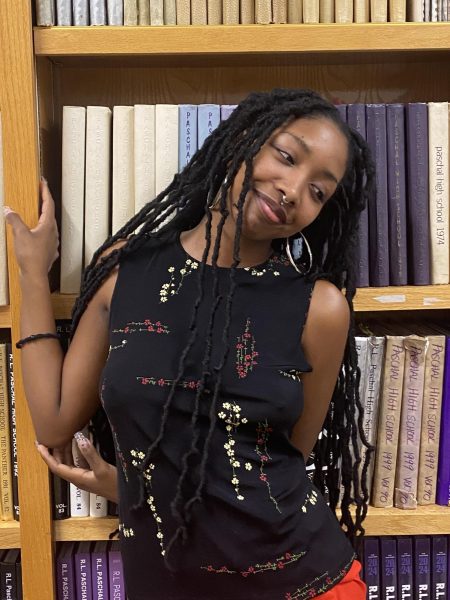

So it’s an honor to have her original art only forty minutes away (hopefully without traffic). Frida: Beyond the Myth, hosted by Dallas Museum of Art, will be there until November 17. The exhibit explores her life and her humanity through her own works as well as the art created by the people who knew her best.

Organized by the Dallas Museum of Art, the exhibition is co-curated by Dr. Agustin Arteaga, the museum’s Eugene McDermott Director, and Sue Canterbury, the museum’s Pauline Gill Sullivan Curator of American Art.

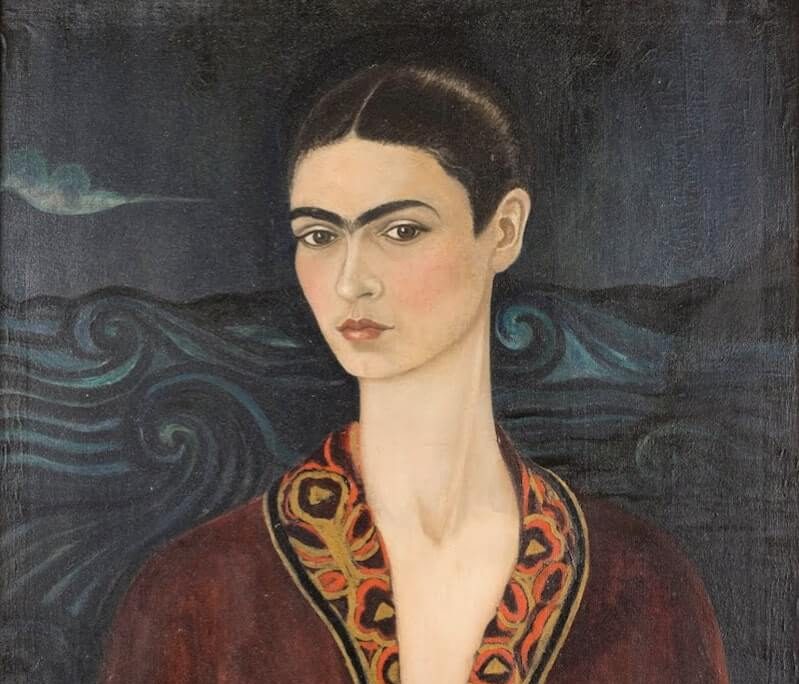

The exhibit starts off with the original drawing and painting of her early days emphasizing the life and death aspects, like in her art. As Well to try to almost visualize the growing person and art as child to a majorly influential artist. The exhibition is made up of sixty works by Kahlo, including her first self portrait, “Self portrait in a velvet dress.” It was created a year after her accident as a gift for her boyfriend at the time, Alejandro Gomez, as a way to remember her as she was recovering from her severe injuries.

In 1929, Kahlo first met Diego Rivera after she asked him to assess her work, and they got married in 1929. The couple moved to the United States where Rivera had several commissions. They spent time in San Francisco, Detroit, and especially New York. The American children in Detroit were interested in Kahlo’s Tehuana dress.

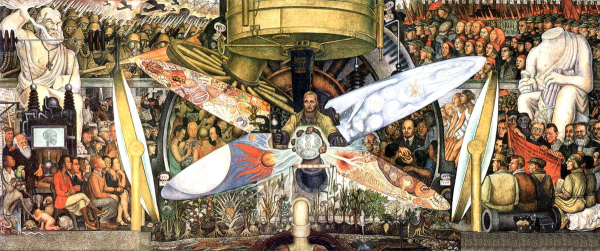

In 1932 while living in New York, the Rockefellers commissioned Diego Rivera to create a mural in the lobby of their flagship 30 Rockefeller building. “Abby Rockefeller, wife of John Jr., had been a longtime fan of Rivera’s; just a year earlier, the Museum of Modern Art, which she co founded, had presented a major retrospective of his work. But as the artist neared completion of his massive “Man at the Crossroads”, John Jr. and his son Nelson were shocked to find an image of Lenin prominently displayed at the center of the mural. The Rockefellers demanded that he paint over the offending portrait; when Rivera refused, the Rockefellers fired him, and ultimately, had the mural destroyed.” cited by rockefellercenter.com.

Following the destruction of Rivera’s controversial Rockefeller Center mural, Kahlo created the painting “My Dress Hangs There” which aimed to depict the superficiality of American capitalism. This painting is filled with the icons of the modern industrial society of the United States but implies that society is decaying and fundamental human values are being destroyed.

Socialist principles had pushed its way into Mexico in the 1920s. A few years earlier, and several leading ideologies of the Mexican revolution had been spreading its message. The triumph of the Russian revolution in 1917, as well as the creation of the Soviet Union in 1922, gave it a major boost. It was no coincidence that the Mexican communist party was founded in 1919. Diego Rivera intentionally put a communist flag on top of the coffin in 1954.

After returning, Kahlo became pregnant numerous times, but Rivera preferred not to have children. One painting reflects Kahlo’s grief after one of her abortions with her artist “palette shaped like a heart.” To recover from one of the abortions, Kahlo traveled from Detroit to Mexico. Lucienne Bloch, an apprentice of Rivera, took a wistful photo of Kahlo staring out of the train window.

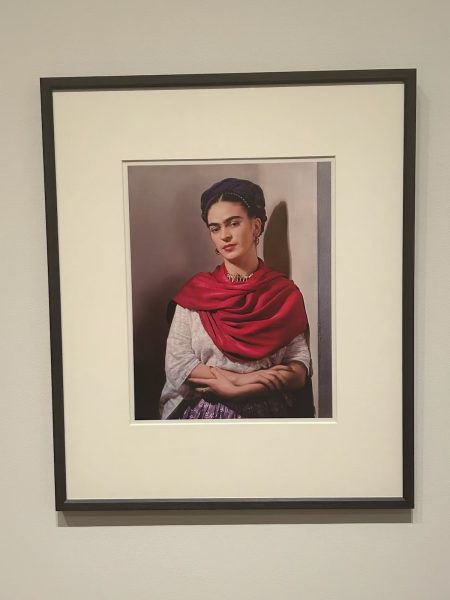

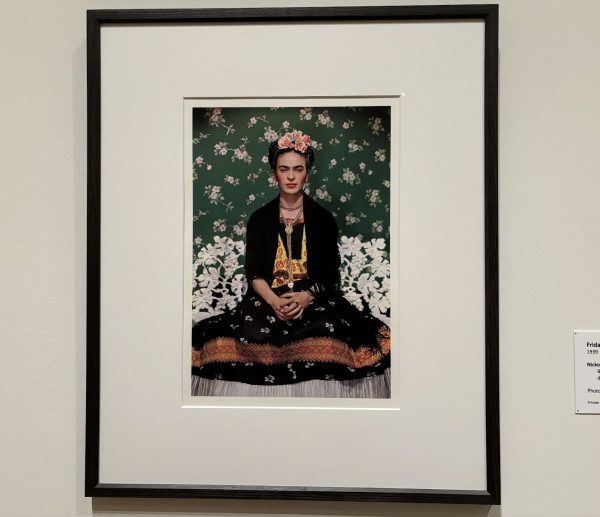

Her relationship with Rivera was complicated, with both pursuing affairs. Kahlo met Nickolas Muray, a Hungarian-born commercial photographer who created some of the most striking photos of her, in 1931 and they had an affair for a decade. Muray hoped to marry Kahlo, but he eventually realized Kahlo and Rivera would always be connected. His portraits reflect the love and respect between the artists.

If you want to learn more about this fascinating artist, check out Frida: Beyond the Myth, at the Dallas Museum of Art!